On Running, Writing, and Life: Some Advice from Haruki Murakami

Exerting yourself to the fullest within your individual limits: that’s the essence of running, and a metaphor for life — and for me, for writing as well.

Sunday morning. 7 AM. I usually don’t set an alarm on Sunday mornings but the bright sunlight bursting through the two large windows in my room is always enough to wake me up. Especially, the summer sun which, even in the early hours, is hot enough. There is a certain harshness to the summer sun even in the morning, unlike the cozy warmth of the sun in the winter. It is the difference between a hot cup of coffee in the summer and the same in the winter. Same coffee. Same me. A different feeling.

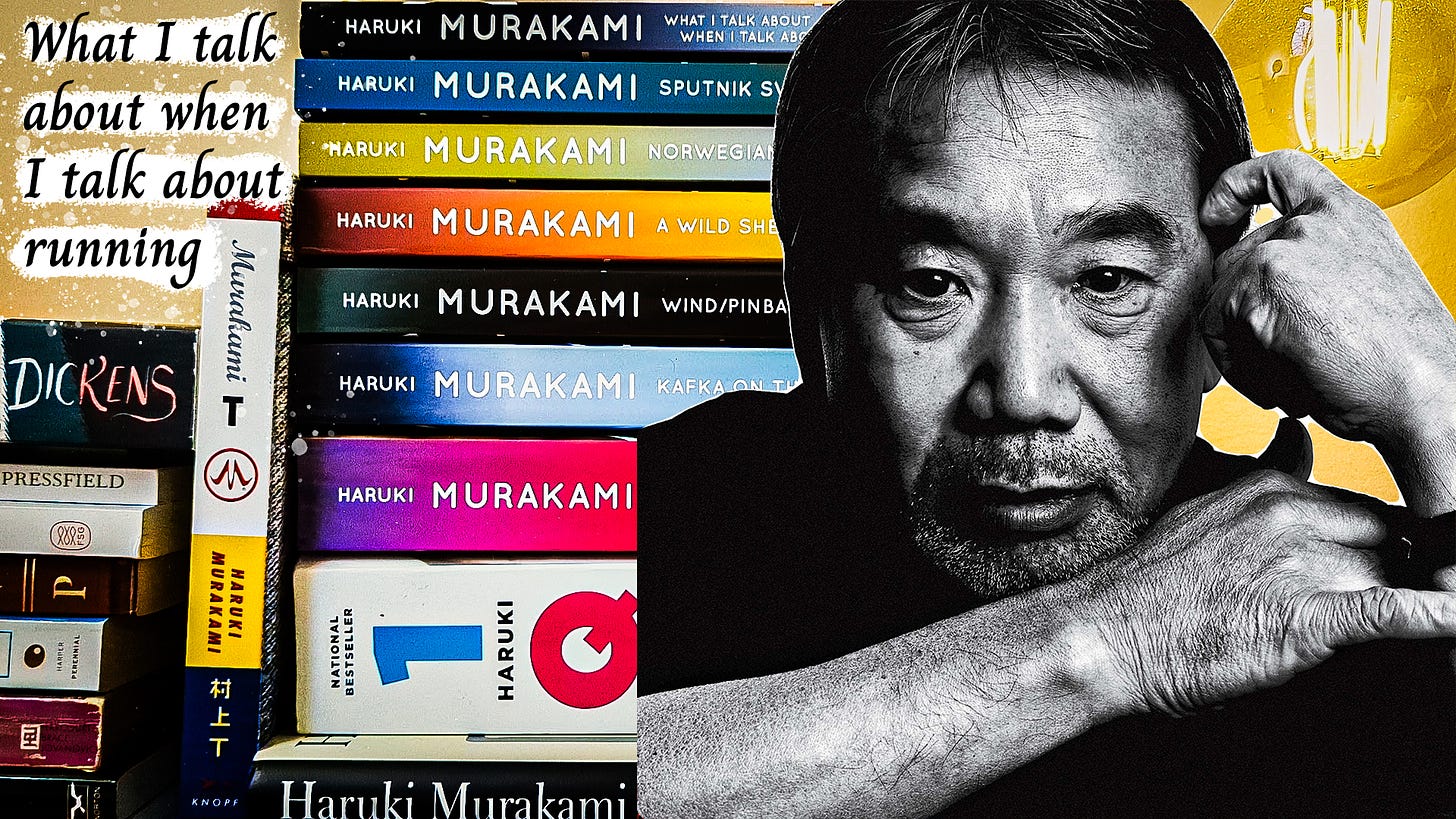

I lie in my bed for another hour, scrolling mindlessly through the news on my phone. Like each morning, the world seems to be on fire. Both literal and metaphorical. My eyes, still tired and groggy, rest on my copy of What I Talk About When I Talk About Running by Haruki Murakami. I get up, swipe it off the bookshelf, and jump back into bed. Enough reality for now. Let me dive a little into what used to be real. The comfortable certainty of the past.

It’s a book about running, technically. A memoir written while Murakami prepared for another marathon. But I always feel Murakami used running merely as a metaphor for life and writing. All the advice he has for running applies well to life and writing. And all the advice he has for writing applies to running and life. I flip through my earmarked copy landing on page 76 where Murakami talks about what he thinks are the important qualities of a novelist.

“It’s pretty obvious: talent.”

How discouraging. Fortunately, he goes on.

“No matter how much enthusiasm and effort you put into writing, if you totally lack literary talent you can forget about being a novelist… The problem with talent, though, is that in most cases the person involved can’t control its amount or quality… Talent has a mind of its own and wells up when it wants to, and once it dries up, that’s it. Of course certain poets and rock singers whose genius went out in a blaze of glory — people like Schubert and Mozart, whose dramatic early deaths turned them into legends — have a certain appeal, but for the vast majority of us this isn’t the model we follow.”

It is quite heartwarming that Murakami includes himself in the “vast majority”. I think about getting up. The sun is getting hotter. But I read on. After talent, Murakami mentions focus and endurance as the two main qualities of a novelist.

“Fortunately, these two disciplines — focus and endurance — are different from talent, since they can be acquired and sharpened through training. You’ll naturally learn both concentration and endurance when you sit down every day at your desk and train yourself to focus on one point… Patience is a must in this process, but I guarantee the results will come… Raymond Chandler once confessed that even if he didn’t write anything, he made sure he sat down at his desk every single day and concentrated… The whole process — sitting at your desk, focusing your mind like a laser beam, imagining something out of a blank horizon, creating a story, selecting the right words, one by one, keeping the whole flow of the story on track — requires far more energy, over a long period, than most people ever imagine.”

I keep the book aside and hop out of bed, feeling a bit optimistic.

I love Murakami. It is interesting that when people say they love a writer, they actually mean they love their work. Sometimes, it may just be that they love one book of that writer that they read at some point. I don’t know how Murakami is in his real life. I have never met him. I have never even seen a video of him talking. I have seen a picture. I have read three of his many books. Yet I say with all my heart: I love Murakami. I love him for A Wild Sheep Chase and I love him for Norwegian Wood. Norwegian Wood might be one of my favorite novels, along with The Great Gatsby and The Moviegoer. All of them, people with talent. Either inborn or acquired.

“Writers who are blessed with inborn talent can freely write novels no matter what they do — or don’t do. Like water from a natural spring, the sentences just well up, and with little or no effort these writers can complete a work. Occasionally you’ll find someone like that, but, unfortunately, that category wouldn’t include me… I have to pound the rock with a chisel and dig out a deep hole before I can locate the source of creativity. To write a novel, I have to drive myself hard physically and use a lot of time and effort. Every time I begin a new novel, I have to dredge out another new, deep hole.”

I can’t ever imagine Murakami having to “pound the rock with a chisel” to write a novel. When I read Norwegian Wood, the love of Toru and Naoko broke my heart yet I couldn’t stop smiling in awe as I soaked the beautifully woven sentences. If hard work can result in such a beautifully written story in the streets of Tokyo, perhaps there is still hope for the rest of us.

I put two slices of whole wheat bread in the toaster and start on my Avocado spread, a Sunday morning ritual. I cut open an Avocado, scoop it out into a bowl, and start mashing with a fork. Salt. Black Pepper. Sesame and poppy seeds. A pinch of red chili flakes. Half a lime and a few drops of olive oil. As the toaster pops the bread out, I’m ready with my spread. A cup of coffee, please. Black. And I’m ready with my breakfast. The smell of freshly squeezed lime, mashed avocado, and coffee brings a comfortable feeling to my morning. A feeling of certainty. A feeling of familiarity.

Certainty and familiarity, two feelings we crave yet can rarely keep for long. Sunday is familiar but Monday brings chaos. As we march out of our castles into the wild, bombarded by a sea of strange faces, it is easy to lose our sense of individuality. We become part of the population and doubt anyone would ever care about our quirks.

“If you think about it, it’s precisely because people are different from others that they’re able to create their own independent selves. Take me as an example. It’s precisely my ability to detect some aspects of a scene that other people can’t, to feel differently than others and choose words that differ from theirs, that’s allowed me to write stories that are mine alone… So the fact I’m me and no one else is one of my greatest assets.”

I put the pile of dirty dishes in the dishwasher and step out of my apartment. The sun is still harsh but at least the wind is cool enough to provide some sense of comfort. The sun hits my eyes, which haven’t seen much daylight since yesterday, like an angry wave crashing into a rock. The good thing about waking up at 7 in the morning is that it takes a long time for noon to arrive, which is still a few hours away. I see a few people getting their mail from the mailbox. Mostly junk magazines and coupons that go straight into the trashcan right next to the mailboxes. Some people are taking their trash out to the big trash can. Calling it a can is unfair though. It is more like a trash room. I think a raccoon has made it its home. The grass still looks dewy from the night.

I see a few people running on the sidewalks, going in various directions, their torsos drenched in varying quantities of sweat. I can’t quite see it from this distance but I’m sure their faces are covered in beads of sweat. It is a good morning for a run. I like to run and actually do run on days my will overpowers my laziness. Not Murakami though. He has been running for years. Marathons and triathlons. Every year. When he wrote What I talk About When I Talk About Running, he had run about 25 marathons and many triathlons. To him, running and writing are made of the same principles. And so is life.

“It doesn’t matter what field you’re talking about — beating somebody else just doesn’t do it for me. I’m much more interested in whether I reach the goals that I set for myself, so in this sense long-distance running is a perfect fit for a mindset like mine.”

As I walk around the block, seeing more people run makes me feel a bit guilty and insecure. I see their perfect running form and their pace and feel like I might never achieve that. How could I ever compete with them?

“The point is whether or not I improved over yesterday. In long-distance running the only opponent you have to beat is yourself, the way you used to be.”

I unlock the door and get inside. The dishwasher is still running, doing whatever it does inside that box. For some reason, I always imagine a dishwasher to work like a laundry machine. All the dishes spinning clockwise and anti-clockwise for an hour until they’re clean. That can’t be true. All the dishes would break each time. That would be one way to get clean dishes each time. I look at my pair of running shoes, lying in the corner, staring at me in disappointment.

“What I mean is, I didn’t start running because somebody asked me to become a runner. Just like I didn’t become a novelist because someone asked me to. One day, out of the blue, I wanted to write a novel. And one day, out of the blue, I started to run — simply because I wanted to. I’ve always done whatever I felt like doing in life. People may try to stop me, and convince me I’m wrong, but I won’t change.”

I fill up a glass of water from the sink and drain it down my throat. The glass goes in the sink, starting another cycle of dirty utensils. I get back to my desk, flip open my laptop, and stare at the screen. I sit motionless for a while, staring at the screen the same way the shoes stared at me, but with fear instead of disappointment. I wonder if someday I'll simply run out of words. The clock next to me ticks away and I keep getting older, second by second. My mind racing through the list of things I want to or have to or need to do. In a tug-of-war between have to and want to, our hearts get constantly torn apart every day. I look at Murakami’s book, still lying carelessly on my bed.

“Most runners run not because they want to live longer, but because they want to live life to the fullest. If you’re going to while away the years, it’s far better to live them with clear goals and fully alive than in a fog, and I believe running helps you do that. Exerting yourself to the fullest within your individual limits: that’s the essence of running, and a metaphor for life — and for me, for writing as well.”

I pick up the book, flip through the pages one last time, and put it back into my bookshelf between the many books still waiting to be read. Perhaps I’ll pick it up again some other morning as yet another feeble attempt to escape reality, knowing well the ephemeral nature of my escape. The only thing real is the past and the present. All else, a figment of imagination.

The sun now blanketed by clouds, I feel a sense of wintry comfort in my room. The clock hits noon. I start writing.